The Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) rescinded a 2018 job offer to run its Dallas-Fort Worth chapter at least in part because the candidate was a Christian.

A year earlier, the staff at CAIR’s New York chapter was so concerned about the behavior of National Litigation and Civil Rights Director Lena Masri, that they debated whether they had an obligation to report her to the state Bar.

In both cases, staffers expressed concern about the harm that could result if these incidents became public. Now they have, but only because CAIR has sued a former employee-turned relentless critic for defamation.

Lori Saroya is “actively engaging in a systemic and continuous internet smear campaign to damage CAIR’s reputation and to cause CAIR severe economic harm,” CAIR said in its lawsuit, filed May 21 in Minnesota federal court. Saroya ran CAIR’s Minnesota chapter from 2007-16, then moved to its national office. She also served on its national board of directors. But she left the organization two years later, and now CAIR and Saroya accuse each other of unprofessional behavior.

In her response to the lawsuit, filed June 11, Saroya included internal CAIR communications showing staffers grappling with sensitive legal issues that they acknowledged could cause the organization significant embarrassment.

Saroya has been active on social media and in reaching out to CAIR allies, accusing the organization – which touts itself as “America’s largest Muslim civil liberties organization” – of discriminating against women in pay and other workplace issues, and of ignoring allegations of sexual harassment. CAIR describes her action as a “media and internet smear campaign” filled with falsehoods.

For example, the lawsuit alleges that Saroya controls an account called “Muslims Documenting Sexism,” which has sent numerous communications asking allied people and organizations not to “partner with the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) or their chapters” because they “documented a pattern of discrimination and abuse inside CAIR.” That pattern includes “Sexual harassment, abuse, and exploitation,” religious discrimination against non-Sunni Muslim employees, a hostile work environment and more.

“CAIR does not use attorneys to ‘suppress, silence, and intimate’ its employees,” CAIR’s defamation suit says, “nor does it engage in a pattern discriminating, harassing, or retaliating against its employees or mistreating them.”

In April, however, National Public Radio reported speaking with “18 former employees at the national office and several prominent chapters who said there was a general lack of accountability when it came to perceived gender bias, religious bias or mismanagement. Many of those interviewed, both men and women, asked NPR not to use their names for fear of legal or professional retaliation.”

The story focused on former CAIR Florida Executive Director Hassan Shibly, and spouse abuse allegations levied by his wife. They are divorcing. Shibly denied all the claims, but acknowledged entering “into religious marriage contracts with women outside his legal marriage.”

One woman, Kyla McRoberts, went on record with NPR to say Shibly “tricked” her into one of those marriage contracts. One night, he cut off her hair “while she slept, angry she had posted a picture of herself online without her headscarf. When she refused sex, she said, he told her that, as his wife, she couldn’t say no,” NPR reported.

Critics say CAIR knew about these and other allegations about Shibly but looked the other way. CAIR denies this claim. Shibly resigned from CAIR in January.

In her response, Saroya also accused CAIR Executive Director Nihad Awad of sexually harassing her, including asking her to meet in a hotel lobby at midnight, where he allegedly said, “Do you know that [other CAIR employees] think there is something going on between us?”

Awad “engaged in the most recent instance in a pattern of unwelcome and highly inappropriate conduct towards Ms. Saroya, which she deflected and did not accept,” her response to CAIR’s defamation suit said. “Days later he continued this conduct, following her around the site of a conference, insisting on sitting next to her every time she moved to a different seat, and pursuing her at the conference.”

Saroya describes the behavior as a last straw for her about the “toxic culture at the highest levels of the organization and at certain CAIR chapters overseen by CAIR, a culture which was exacerbated by a culture of impunity.”

Hush Money

CAIR, Saroya’s response claims, “spends substantial amounts of donors’ money in order to threaten, intimidate and sue those who have the courage to speak about CAIR’s culture of discrimination and misogyny,” and pay settlements in exchange for their silence.

She cited one instance in which a settlement was offered to cover up a possible act of religious discrimination.

In 2018, CAIR offered its Dallas-Fort Worth executive director position to attorney Karen Hernandez. CAIR’s board was comfortable with her, a separate lawsuit filed that year in Texas claimed. But Awad stepped in “and expressed that he would not allow her appointment because he found her to be not pro-Palestine enough and that her writing on domestic violence was ‘vulgar and disgusting.'”

According to Saroya’s response, Hernandez had written openly about surviving domestic violence.

If the offer to Hernandez was not withdrawn, Awad “threatened to dis-affiliate CAIR-National from CAIR-DFW,” the Texas lawsuit said. That suit, brought by Rifat Malik, a former Dallas chapter board member who said she was tapped to serve as interim executive director in 2017 “amidst allegations of unethical conduct and mismanagement” there, was abruptly withdrawn in April 2019.

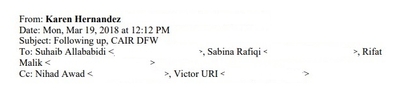

Saroya’s June 11 filing includes an internal CAIR email in which Hernandez informed the organization that she had hired a lawyer because CAIR placed her in “professional and financial peril.”

“I have been more than kind and patient in this process and it is due to CAIR DFW’s gross mismanagement that I am in this position,” Hernandez wrote in the March 2018 email. “I’d hate for word to get out as to how I’ve been treated and that CAIR DFW’s donors insisted I not be Executive Director because I’m not Muslim, and that the Board caved to their demands.”

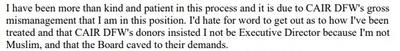

Saroya’s response also includes a subsequent email from Danette Zaghari-Mask, CAIR’s nonprofit and compliance attorney, who suggested paying Hernandez $10,000 in two payments spaced five months apart, “with a non-disclosure agreement.”

“The most serious risk she presents right now is in the form of public pressure and defamatory speech against” the Dallas-Fort Worth chapter, Zaghari-Mask wrote.

Urgent Ethical Issue

In April 2017, the executive director and general counsel for CAIR’s New York chapter wrote to the national board about an “Urgent need to address unethical conduct by CAIR National’s Legal Department.” The letter, which Saroya included as an exhibit in her response to CAIR’s lawsuit, was included to show “examples of internal complaints of CAIR staff making ‘serious mistakes’ on legal matters,” a claim CAIR accused Saroya of spreading falsely.

Masri, CAIR’s National Litigation and Civil Rights director, was part of the legal team in a 2017 case, Sarsour v. Trump, that challenged the new administration’s “Muslim ban.”

“As both we and Ms. Masri are licensed in New York, we may soon be forced to report such unethical conduct to the New York State Bar,” the letter from Afaf Nasher and Albert Fox Cahn said. “This is an extraordinary step, and one we would only consider as an absolute last option. We are distressed beyond words to think that we may be forced to publicly report internal misconduct, especially given the likely fallout from such a public investigation. Sadly, for us, such disclosure may soon no longer be optional.”

Masri, they wrote, “repeatedly made significant decisions about” case strategy “without the required consultation with her clients.” That includes filing an amended complaint and a petition for a temporary restraining order. She “made false or misleading statements in calls with, or emails to, CAIR staff,” some of whom were among the plaintiffs in the case. “It is hard to overstate just how grave an ethical breach this is,” Nasher and Cahn wrote. She claimed to have consulted with “dozens of experts” on a draft complaint, but could name only one, whose practice isn’t related to the case. She also told CAIR officials in writing that the legal team “retained one of the largest law firms in the country … that has given us over 30 pro bono attorneys to help with our case.” The firm agreed to help in exchange for anonymity, she said.

“Such a secret arrangement, if it existed, would be blatantly unethical,” Nasher and Cahn wrote. But the filings were so shoddy, they doubted the claim was legitimate. Either way, it would be unethical to hire such counsel “without client notification or consent.” Masri initially rebuffed efforts to learn this law firm’s identity.

Saroya’s response does not indicate what happened next – whether the issue was brought to the Bar’s attention or if other information assuaged the New York chapter’s concerns.

Masri is still on the job. (She is counsel in a libel suit against an IPT staffer in Maryland federal court.)

Saroya’s response indicates that she is not cowed by CAIR’s litigation. If anything, she seems eager to have her allegations debated openly in court.

“CAIR maintains a culture of misogyny,” her response said, “that it has been dishonest and misleading with its donors, whose contributions it has frequently misused for the purpose of silencing critics, that its leadership has been dishonest with and breached its fiduciary duties to the CAIR Board, that it has violated basic rules of good governance and mismanaged the enterprise, all to the detriment of the causes about which it professes to care.”

This column was originally published at The Investigative Project on Terrorism.

The views expressed in CCNS member articles are not necessarily the views or positions of the entire CCNS. They are the views of the authors, who are members of the CCNS.